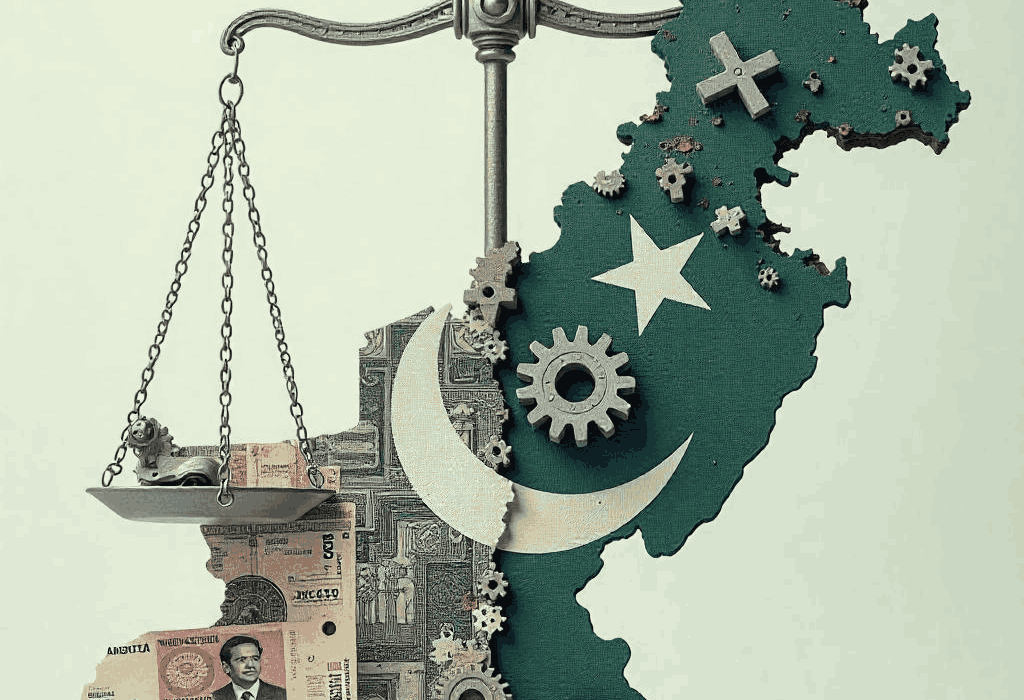

Pakistan’s recurring engagement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has long been a point of debate. Is this reliance rooted in deep structural flaws in the economy, or is it largely the result of political mismanagement? With every economic downturn, Pakistan knocks on the IMF’s door, seeking financial support to stabilize its deteriorating balance of payments. But what lies at the heart of this repeated cycle?

In this blog, we explore whether Pakistan’s IMF dependency is a structural economic issue or a political one or perhaps, a blend of both.

A Long History of IMF Bailouts

Pakistan has approached the IMF further than 20 times since the late 1950s. These bailout packages have aimed to ease immediate liquidity pressures, strengthen foreign reserves, and help meet debt scores. Each program comes with IMF loan conditions ranging from reducing the financial deficiency and adding duty earnings to removing subventions and floating the exchange rate.

Still, the frequent return to the IMF suggests that these measures have n’t had a continuing effect. The country’s failure to break out of this cycle raises a pivotal question: Why can Pakistan sustain profitable stability without external help?

The Structural Side of the Equation

One school of thought attributes the IMF dependency to structural economic weaknesses that have been ignored for decades.

1. Narrow Tax Base

One major structural flaw in Pakistan’s economy is its persistently poor tax-to-GDP ratio, hovering about 9–11%. Low tax compliance exists even inside the formal sector; much of the economy runs in the informal sector. Lacking sufficient income, the government fights to pay for social services and development initiatives without borrowing.

2. Chronic Trade Deficit

Pakistan’s export base is narrow, dominated by low-value goods like textiles. Meanwhile, its import bill remains high due to oil, machinery, and food products. This persistent trade imbalance contributes to the balance of payments crisis, leaving the country vulnerable to external shocks and reliant on borrowing to fill the gap.

3. Debt Servicing Pressures

Public debt has crossed 70% of GDP, and debt servicing eats up a massive chunk of government revenue. With limited fiscal space, Pakistan is often forced to borrow more just to meet existing debt obligations, a classic debt trap that increases dependency on IMF support.

4. Energy Sector Deficits

The circular debt in the energy sector has ballooned over time due to inefficient pricing, theft, and outdated infrastructure. This not only affects the budget but also limits industrial productivity, feeding into the broader economic stagnation.

These structural issues require long-term, consistent reform, something that IMF programs attempt to nudge, but rarely succeed in due to another major factor: politics.

The Political Dimension

While the economic problems are real, the failure to address them often lies in the political domain. Successive governments have been reluctant to take tough decisions that might hurt their popularity, especially in the short term.

1. Populism vs. Reform

Subsidies on fuel, electricity, and essential commodities are politically popular but economically damaging. Attempts to withdraw them, even under IMF pressure, often result in protests and political instability. As a result, governments delay or dilute reforms, undermining long-term recovery.

2. Lack of Policy Continuity

Each new government tends to reverse or stall the programs of the former bone . This lack of durability in profitable policy in Pakistan disrupts reform progress. IMF conditions are occasionally accepted simply to unlock backing, only to be abandoned when the political cost becomes too high.

3. Weak Institutions

Pakistan’s governance challenges including corruption, weak regulatory oversight, and lack of institutional autonomy further complicate reform implementation. Even when policies are in place on paper, enforcement remains a major hurdle.

4. External Political Calculations

Geopolitical considerations also play a role. At times, the IMF and other global lenders have extended favorable packages due to Pakistan’s strategic importance. This can create a moral hazard, where structural issues are sidelined because short-term funding continues to flow regardless of reform.

IMF Loan Conditions: Boon or Burden?

Critics argue that IMF programs often impose austerity that deepens the economic pain for ordinary citizens leading to inflation, job losses, and public unrest. However, defenders maintain that IMF loan conditions are necessary discipline for governments that have long avoided reform.

In Pakistan’s case, it’s often a mix of partial reform and backsliding. The country agrees to tough measures, such as raising electricity tariffs or imposing new taxes, only to ease up once the immediate tranche is disbursed.

This creates a stop-start reform cycle that never addresses the root causes, leading to recurring crises and repeated bailouts.

So, Structural or Political?

The truth is, Pakistan’s IMF dependency is both structural and political.

- The structural flaws — low productivity, narrow tax base, high energy sector losses, and a chronic trade deficit — are undeniable.

- But the political unwillingness to address these flaws, especially when elections are near or coalitions are fragile, turns manageable problems into chronic ones.

The IMF does not create Pakistan’s economic problems, but it has become a crutch used to delay meaningful reform.

The Way Forward: Breaking the Cycle

To move beyond IMF dependency, Pakistan needs a coordinated, long-term strategy that includes:

- Expanding the tax net to include under-taxed sectors like agriculture and retail.

- Boosting exports by supporting value-added industries and modernizing infrastructure.

- Fixing the energy sector through pricing reforms, loss reduction, and renewable energy investments.

- Improving governance by strengthening institutions, reducing corruption, and ensuring policy continuity.

- Depoliticizing economic policy, possibly by empowering independent fiscal councils or technocratic bodies to oversee critical reforms.

Public awareness and stakeholder engagement are also key. People are more likely to accept short-term pain if they see a transparent roadmap for sustainable growth.

Final Thoughts

Pakistan’s repeated passages to the IMF reflect deeper profitable vulnerabilities, but also a harmonious political failure to fix them. Until structural reforms are treated as anon-negotiable public precedent rather than as burdens assessed by external lenders the country will remain wedged in a cycle of extremity and bailout.